Description

“Minstrels and rags – grow on a stump“, says a contemporary proverb. The medieval minstrels were both: welcome and popular entertainers and social outsiders, whose lifestyle people tended to view with disgust. Their mobility and itinerant life stood in stark contrast to a well-ordered world defined by sedentarism, hierarchy of estates, and guild compulsions.

In the 14th century, Alsatian minstrels had formed a large professional association. This kingdom of traveling people was under the protection of the powerful lord of Rappoltstein, to whom the minstrels were liable to pay taxes, and who in return undertook to look after their interests and protect them against encroachments from outside. In order to reconcile themselves with the Church, they chose Mary as their patron saint and gathered annually for Piper’s Day in her honor.

At the head of the kingdom was the Piper King: he had the task of keeping order among the colorful crowd of musicians and watching over the observance of the guild rules. Equally, however, he was also the chief justice of the Piper Court, a separate jurisdiction of which the minstrels were particularly proud.

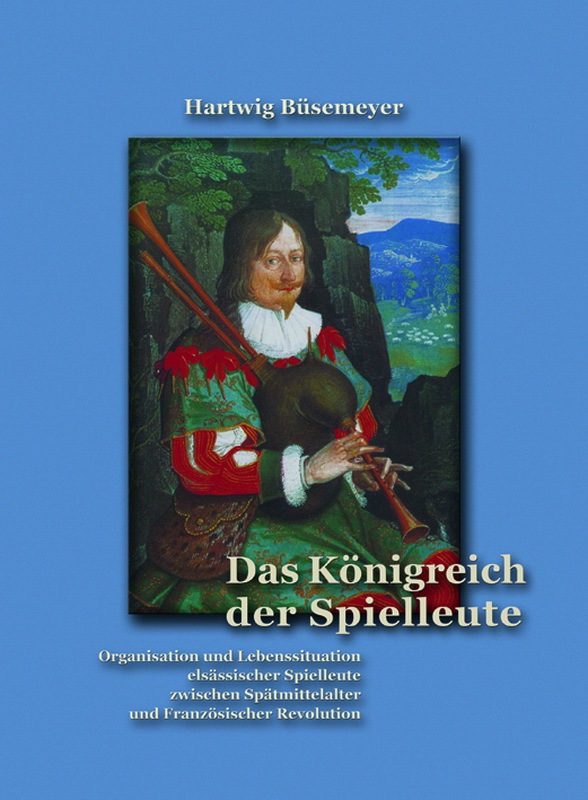

In this book, Hartwig Büsemeyer presents the history of the brotherhood of Alsatian minstrels over the entire period of its history – from the end of the 14th century to the French Revolution.

The main focus of his work was the study of small-scale life and everyday culture of minstrels. The reasons that led to the slow decline and dissolution of the brotherhood, the author was able to very accurately depict with the help of previously unpublished sources from the archives of Colmar and Strasbourg.

Hartwig Büsemeyer, born in Bielefeld in 1953, lives in Esslingen near Stuttgart. In 1977, together with friends, he founded the group Spielleut, which performs early music in concert on replicas of historical instruments. In this ensemble he appears mainly as a woodwind player, playing various bagpipes, shawm, cornamuse, gemshorn, krummhorn and flute. As an author, he became involved with historical minstrels at an early age. Here he soon became particularly interested in Alsatian musicians.

Content:

The hardcover edition with dust jacket contains over 90 illustrations, an extensive glossary, detailed source references, and an index of illustrations used. A review of this title appeared in Revue d’Alsace No. 131, 2005 by Georges Bischoff. The German translation of the review can be found in the reading sample for this book or in the download area of our homepage.

On October 1, 2006, Hartwig Büsemeyer received the prestigious Alsace Prize of the Académie d’Alsace, which is sponsored by the city of Schongau, for his work. Every two years, the Akadémie d’Alsace awards this prize to authors who have rendered outstanding services to Franco-German cooperation and understanding.

Order no: 65-0

ISBN: 978-3-927240-65-0

Format: 19 x 26 cm

Number of pages: 246 pages

Binding: Hardcover with dust jacket

Review of the book by Hartwig Büsemeyer “Das Königreich der Spielleute” – Organization and life situation of Alsatian minstrels between the late Middle Ages and the French Revolution – published in Revue d’Alsace Nr. 131, 2005 by Georges Bischoff

This is a welcome book. First, because of the exterior: a good binding, a flawless page layout, well-labeled illustrations, very readable texts with well-considered footnotes, an index of places, an index of persons, etc. Secondly, however, and above all because of the content, which on the one hand illuminates the representational and musicological aspect, but on the other hand is also sophisticated in terms of popular science.

And indeed, the material is of considerable size. The history of minstrels in Alsace has long been described by authors who wrote it as a brief overview in the 19th century. treat. If one follows Vogeleis, who is still the bible of the history of music in Alsace, the bibliography of the subject has hardly increased since then, either because it was simply ‘cloned’ or because only short essays came out in specialized journals.

The importance of the work is based on the thematic overview starting from the question of the origins, organization and working conditions of the regional brotherhood, which is called by the somewhat medieval term ‘minstrels’. In total, there are 11 chapters in three major sections. It begins with the report that deals with the establishment of the fraternal institutions, a process that cannot be dated precisely but that took place occasionally at the Council of Basel, and was – probably – modeled on other regional communities (e.g. the boilermakers or the shoemakers). The first sovereign document granting the lords of Ribeaupierre a guardianship over the itinerant musicians dates back to 1481, but their role became more and more important in this distant epoch, as it is proved by documents of Maximilian I and his father Bruno towards the end of the 14th century. underline. The territory that was transferred to them is precisely circumscribed as Alsace between the ridge and the Rhine, the forest of Haguenau and the foothills of the Jura, which incidentally invites us to reflect on the identity of this region, which is not necessarily the ‘Upper Rhine’, on the two banks – the right, incidentally, had its own brotherhood centered on Riegel in Breisgau and under the official protection of the Counts of Württemberg (1458). Incidentally, the center of the Middle Alsatian brotherhood can be assumed to be Ribeauvillé (first, it seems, Villé) as its headquarters, although a decree of Guillaume II of Ribeauvillé actually establishes three ‘cercles’ (circles), in the north around Bischwiller or Rosheim, in the south around Alt-Thann (p.48). In his capacity as patron saint of ‘flying’ musicians, the Lord of Ribeauvillé apparently levies a sensitive fee (the story of which could be elaborated) and exercises his delegated authority with the help of an organization headed by a ‘Pfifferkunig’.

If the list of masters remains incomplete, it can be concluded that they acquired a great reputation, mainly in the modern period – the last of the series was Francois Joseph Wuhrer (who held the post of organist and French schoolmaster) between 1787 and the Revolution, and who received his musical training in the French gendarmerie in the garrison of Lunéville.

The brotherhood, which placed itself under the protection of the Virgin, which played a central role especially on the occasion of the pilgrimage of Dusenbach – and is written down in the statutes of 1606 – had altars in several other places (especially in Alt-Thann or in Strasbourg). Did the ups and downs associated with the Reformation have an impact on minstrels? The question remains. On the other hand, the fraternal functioning can be fairly well traced since the order of 1494, renewed, among others, in 1606 (complete text in both languages in a printed version of 1784 on pages 72-75). One learns about the regulations that established a great institutional continuity (for example, by returning the insignia and the best instrument of a deceased brother as a kind of bequest to the fraternity) and, of course, the discipline and duties of the association.

The activities of the brotherhood are widely described against the background of the archives visited (pp.220-221), as well as the main development in modern times, especially in the 18th century. On what precedes this, much could undoubtedly be found elsewhere – in the minutes of Obernai or in the scattered legal yearbooks and in the decrees issued by the municipal authorities (such as those of Council XXI in Strasbourg, which are a veritable gold mine in this field). The author describes the heyday of this brotherhood, especially Pfiffertag, which is the subject of an extensive chapter (fortunately with a map showing the places of origin of the 135 participants in this annual meeting, p. 126), but unfortunately the choice of images is very scarce here. The central question of the coexistence of a popular culture and an official high culture is the focus of the last three chapters of the book: the excursus on repertoire could be enlarged, especially on the changes in keys, melodies, dance steps, instruments. What about the migrations of Alsatian musicians to other cultural regions, e.g. to French countries and vice versa, before the French conquest? Likewise with the shepherds’ festival of Froideval near Belfort at the beginning of May or with the numerous kilbs of the region?

The abundance of the executed work of H. Büsemeyer must not obscure the view for what still remains to be done or to be put right (in the index Guillaume and Wilhelm von Rappoldstein are different persons; Werner Burggraf p.44 becomes Burggraf Werner etc.). The contribution of archaeology and heraldry can be improved in several ways. Thus, the excavations of the Serpent drugstore in Strasbourg (whose publication is announced by Maxime Werlé) have revealed frescoes of the 14th century. brought to light, which depict several musicians. Likewise, the author could have reproduced the bagpipe, which serves as a chivalric emblem of the lands of the Ribeaupierre, and which dates back to the 16th century. originates and is kept in the archives of Innsbruck.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.